Picture this: you’ve just walked through an exhibition of Frida Kahlo’s possessions and paintings in the Victoria & Albert Museum, experiencing it amongst others who are just as hushed and awed as you. The lights are fairly low, everyone is moving slowly; we are truly taking everything in, genuinely awe-inspired by every piece and the way they bring this incredible woman to life in front of us.

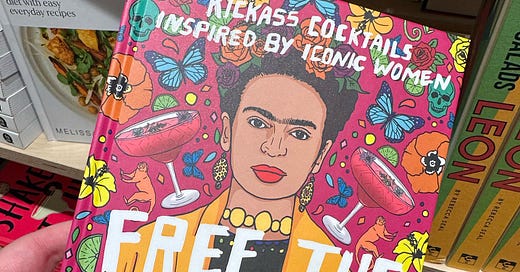

Suddenly, you turn a corner and you are immediately brought out of that bubble into harsh lights, loud voices. You have been flung into a gift shop full of, largely, what can only be described as tat - plastic flower crowns, irrelevant bright books, and endless screen printed tote bags at £20 a piece. The transition between the two is not only jarring sensorily, but they feel completely antithetical - how can a woman so clearly communist who’s art protested against this commodification possibly be used this way?

This was in 2018, and was the first time I realised how deep the commodification of Frida Kahlo goes, after a decade of idolising her. When I was in Year Four, I made a scrapbook where I painstakingly copied out her art and information from books my mum kept at home. I didn’t know I was disabled at the time - two years later, I would begin my journey to understanding I was physically disabled - but I felt an affinity with Kahlo that has come to make much more sense as a grown-up who knows they are queer and multiply disabled, and is unashamedly anti-capitalist.

I bought a little badge to mark the memory of the visit, muttering about the extent of how much rubbish was being sold in her name.

Since then, I see it everywhere. It is endless. Frida Kahlo is the ultimate boss-babe, destined to be made into feminist cocktail recipes, make-up brush sets, and flower vases, not to mention endless fast-fashion t-shirts that were likely made by oppressed women being paid pennies. “A stocking filler favourite!”, the makeup company exclaims about a brush that features just a monobrow and a red lip; her art is, of course, nowhere to be seen, nor any of her words, taking away her humanity and cutting it down to only two of her features.

A moment to consider disability justice

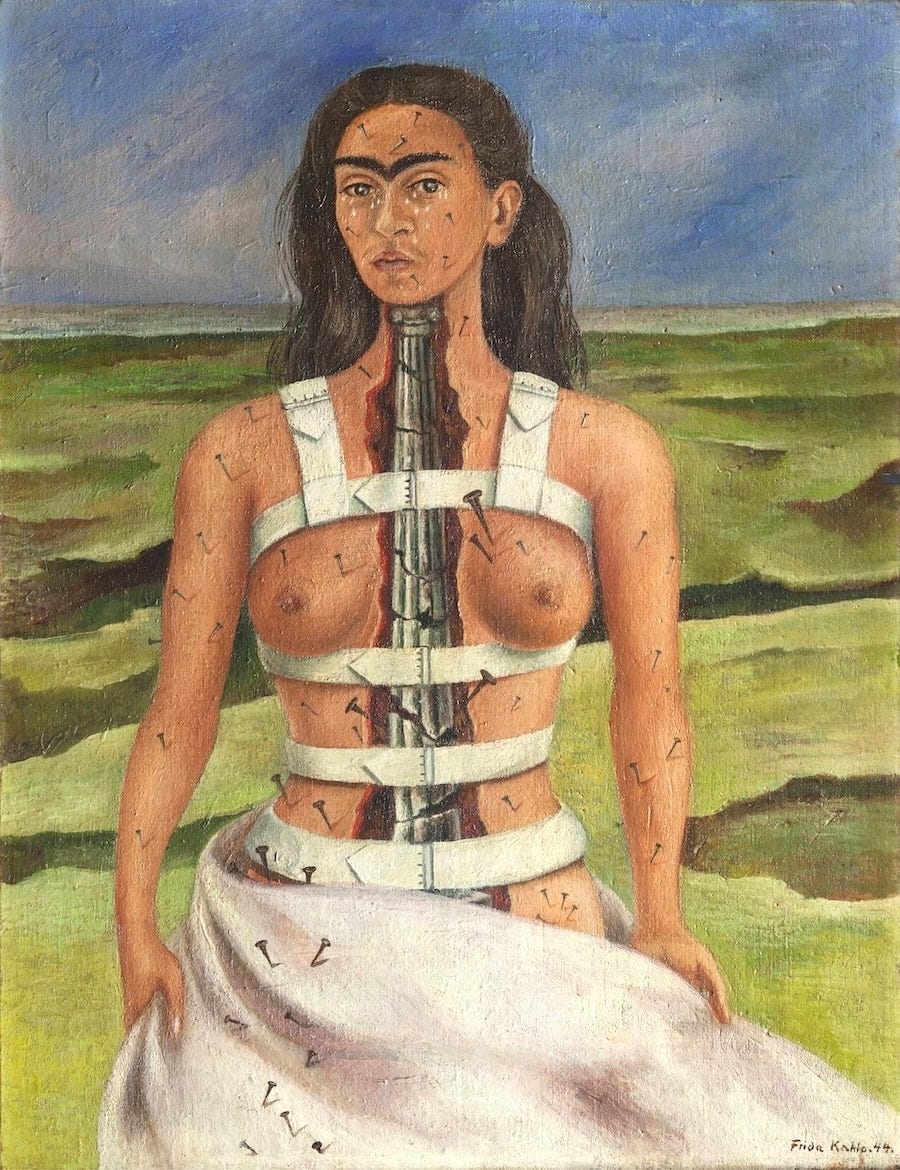

In understanding Frida Kahlo and her politics, we must understand her experience as a disabled and queer woman of the global majority. Kahlo was disabled in her childhood by polio, but she was also significantly disabled by a bus accident in 1925, where an iron rod skewered through her hip and vagina; causing significant fractures, crushes, and dislocations. It was during this that her mother attached a mirror to her bed and gave her materials to paint with, and she began to paint self-portraits and portraits of her family, as well as studying art history.

When we discuss disability justice, we refer to the 10 principles, which directly include anti-capitalist politics: the ways our non-conforming bodyminds push against a society that seeks to profit from people as resource1. In the case of Kahlo, these cannot be separated: what she could produce was directly linked to her non-conformity, and later used as resource in ways she did not consent.

One of the other principles is intersectionality and the recognition of the way we do not lead single-issue lives: it must be acknowledged that some of the fascination and fetishisation of Frida is directly linked to her ethnicity and race, including that of how she kept her unibrow, and the ways she wore makeup, as well as the fetishisation of her accident.

There was ableism woven into Kahlo’s experience of the world, much like there is for many of us, including at her own wedding. Her experience of miscarriages and pregnancy loss, shown in many of her paintings, are heavily intertwined with her existence as a disabled woman, and we also see many pieces of work portraying her use of orthopaedic braces and mobility aids. To attempt to separate disability from her, like almost all of the ways she is commodified, is erasure.

Kahlo’s commitment to communism

Fundamentally, both Kahlo and her husband Diego Rivera were communists. Although the latter was expelled from the Communist Party for working with the Mexican government, and Kahlo left in solidarity, these beliefs were still clear through their respective works and their decision-making, including supporting Trotsky’s asylum in Mexico after being expelled from the USSR.

In 1948, Kahlo became once again part of the Mexican Communist Party, and this became core to her life and to her painting into the early 1950s closer to her death. In 1951, she wrote that she wanted her painting to turn into something ‘useful’, as she felt all she had done with it was ‘express herself, which, unfortunately, has been of no use whatsoever to the Party’2. It is severely evident that this was her priority at this point in her life - her art doing whatever it could to shift capitalist natures.

‘I must fight with all the strength I have to ensure that the little positive effort my illness allows me also serves the Revolution. That is the only reason for living’3

In her published diary, there are consistent references to communism and anti-capitalism. Oppression and capitalism (which are, of course, intrinsically linked, as we understand within disability justice, amongst other movements) are mentioned across much of her work, fundamentally pushing against issues that are akin to her own eventual commodification.

‘I’m convinced of my disagreement with the counter-revolution - imperialism - fascism - religions - stupidity - capitalism - and the whole gamut of bourgeois tricks - I wish to cooperate with the Revolution in transforming the world into a classless one so that we can attain a better rhythm for the oppressed classes’4 (1950)

In 1952, her diary muses on her life and contributions to the party, including a shift to seeing her work as ‘revolutionary realism’5, and she notes that she had been sick since she was six years old and had never enjoyed health for more than a short period in order to be useful - this, and her commitment as she continued towards end of life, is reiterated constantly.

Kahlo’s death ultimately came four days after attending a Communist march in 1954 whilst ill with pneumonia - reading her diary, some argue this was a form of suicide or assisted dying; others would argue it to be her die-hard allegiance to her politics. Her beliefs simply cannot be separated from her.

Commodification is a failure

When we commodify figures like Frida Kahlo, we lose sight of their roots and the means of oppression. It is no coincidence that many artists and creatives have been left-wing and communist; art is a means of resistance as it certainly was for Frida Kahlo.

When she becomes a cocktail recipe based on “badass women” or her eyebrows are printed onto a kabuki brush, we do her a disservice. We take her messaging and squeeze it down into something profitable, not allowing those new to her world to see the realities that she saw as a multiply disabled, queer, racially marginalised woman.

Amongst this commodification, I rarely even see her art. This is a woman who dedicated her life to painting, and yet, now, she is only allowed to be her eyebrows or, at best, people’s morbid fascination with her accident?

This commodification is not new. In 2001, Stephanie Mencimer wrote that had she been born slightly later, her ‘self-esteem could have been bolstered by any number of Frida storybooks, paper dolls, and art kits now available for millennial children in need of a unibrowed role model’6. She also talks of an exhibition at the time where visitors left with memorabilia - not unlike my own experience 16 years later.

‘Learn that I am nothing but a “small damned” part of a revolutionary movement. Always revolutionary, never dead, never useless’7

Ultimately, Frida Kahlo’s memory deserves us pushing back against this commodification and using her nature for capitalist activities - not only as someone with opposite beliefs, but as a figure who simply deserves to be more, with her history and beliefs respected.

History has to be a part of revolution and liberation - the taking and twisting by capitalism of figures that represent us is not an accident.

References

Alcántara, I., Egnolff, S. and Clough-Laub, J. (2016) Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera. Munich: Prestel. p.100

ibid.

Kahlo, F., Fuentes, C. and Lowe, S.M. (2005) The Diary of Frida Kahlo: An intimate self-portrait. New York: Abrams. p.251 translated, p.93 source.

Kahlo, F., Fuentes, C. and Lowe, S.M. (2005) The Diary of Frida Kahlo: An intimate self-portrait. New York: Abrams. p.255 translated, p.104 source.

Mencimer, S. (2001) The trouble with Frida Kahlo, Washington Monthly. Available at: https://washingtonmonthly.com/2001/06/01/the-trouble-with-frida-kahlo/ (Last accessed: 03 March 2025).

Kahlo, F., Fuentes, C. and Lowe, S.M. (2005) The Diary of Frida Kahlo: An intimate self-portrait. New York: Abrams p.251 translated, p.93 source.

Thank you for sharing this great piece. I agree completely. I also got the badge at the V&A exhibition, like you. I liked that it just had a quote of hers. No picture, no name, just: I am my own muse. Back to the basics, the essentials of what made her so great.

This is amazing. Thank you so much for taking the time to write this. I've got an upcoming art workshop that I'm doing, and I'll be sharing this when we talk about Frida and mass consumption of art. <3